Student Data Shows Unsafe Arsenic Levels in ME Wells

An alarming 10% of Maine’s private wells are contaminated with arsenic, and many of the people who drink from those wells are unaware1. It’s likely that around 38,000 Mainers unknowingly ingest private well water with arsenic above the Environmental Protection Agency’s maximum contaminant levels. That’s because only 56% of wells in Maine have been tested for arsenic. 2

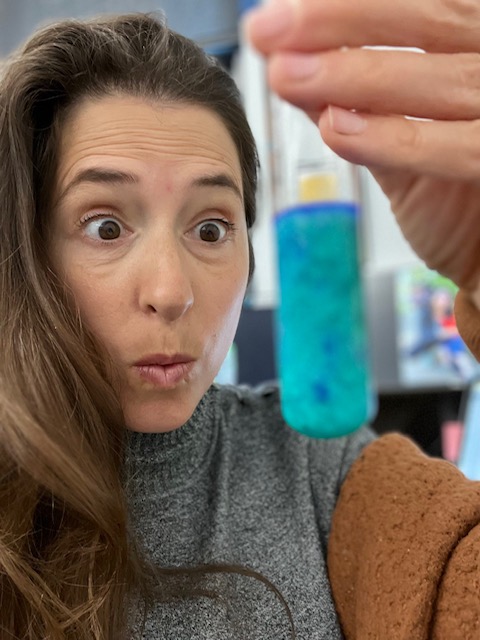

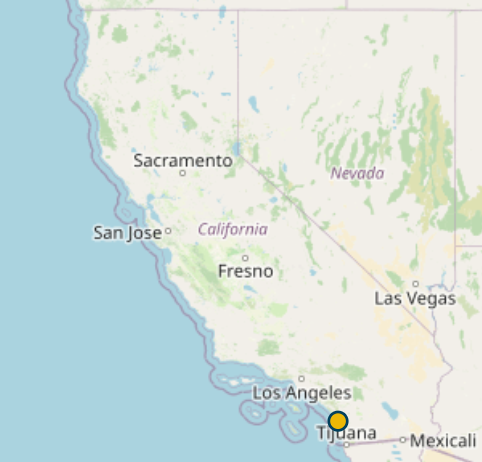

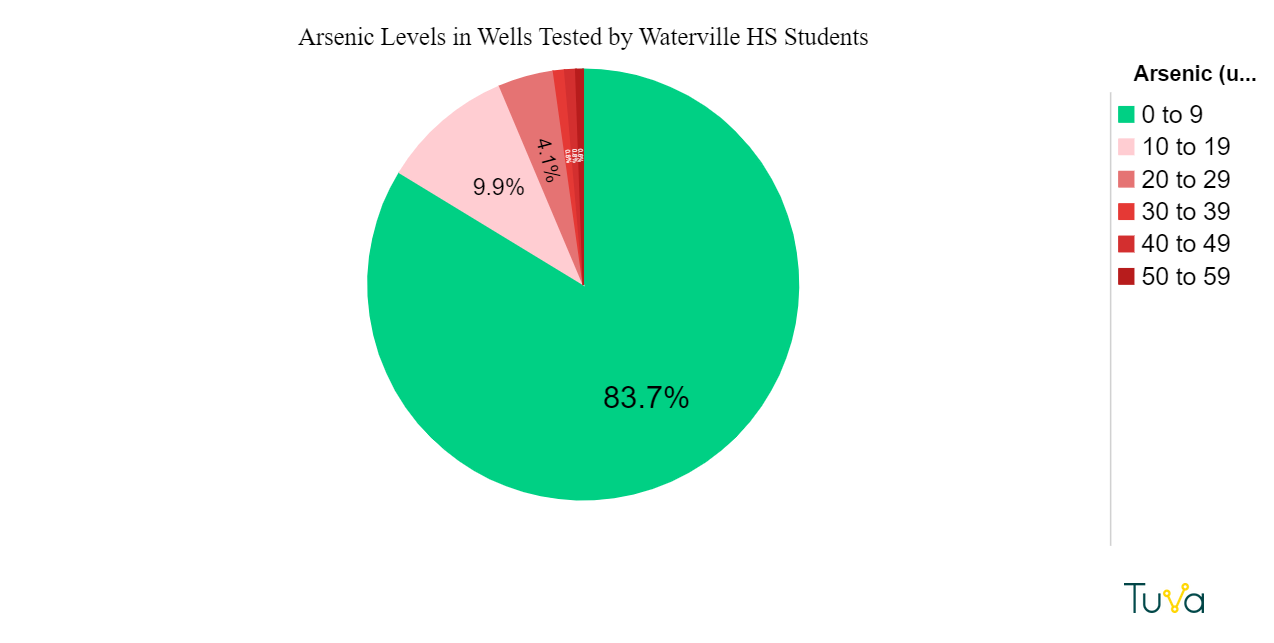

Students in Jon Ramgren’s high school chemistry class are helping change that. Since 2018, Ramgren’s classes have tested more than 350 wells in the vicinity of Waterville Senior High School in south-central Maine. 16% of the wells his students have tested contained unsafe levels of arsenic, a known poison and carcinogen.

The ME Department of Environmental Protection deems arsenic levels greater than 10ug/L unsafe.

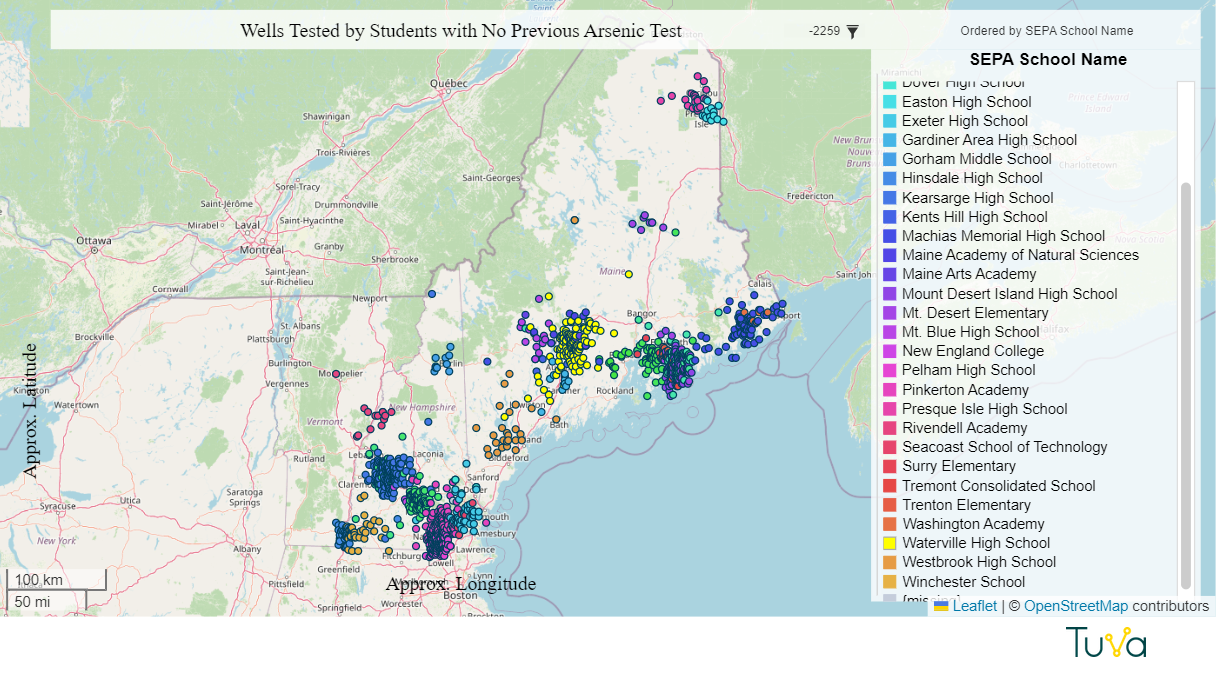

Ramgren was one of the first teachers to join All About Arsenic+, a school-based citizen science initiative begun in 2015 by Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory and Dartmouth College’s Toxic Metals Superfund Research Program. Students have tested thousands of wells in Maine and New Hampshire as part of this project, which is funded by a National Institutes of Health Science Education Partnership Award.

“We are getting real-world data that no one has; we are adding to data that is limited, “ said Ramgren.

All sites on the map represent wells that hadn’t been tested for arsenic prior to the project. Data points in bright yellow show the locations where water samples were collected by Waterville students.

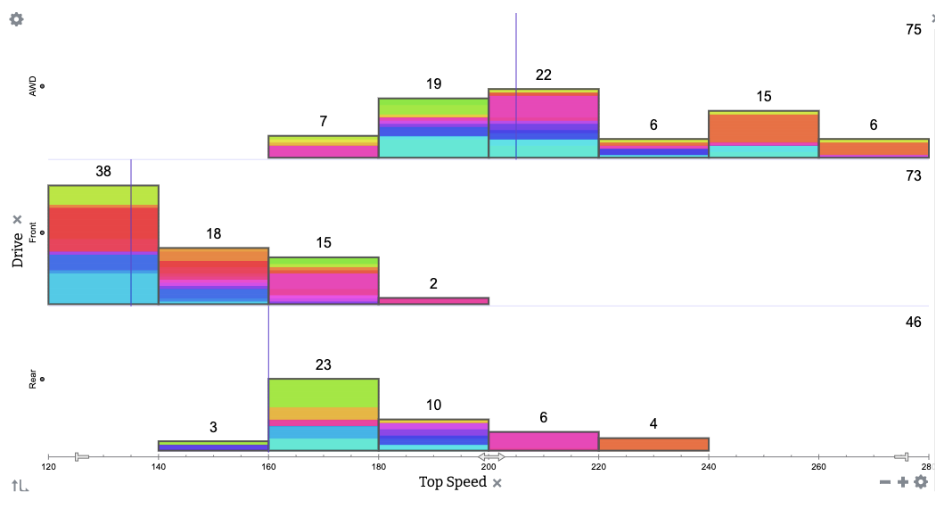

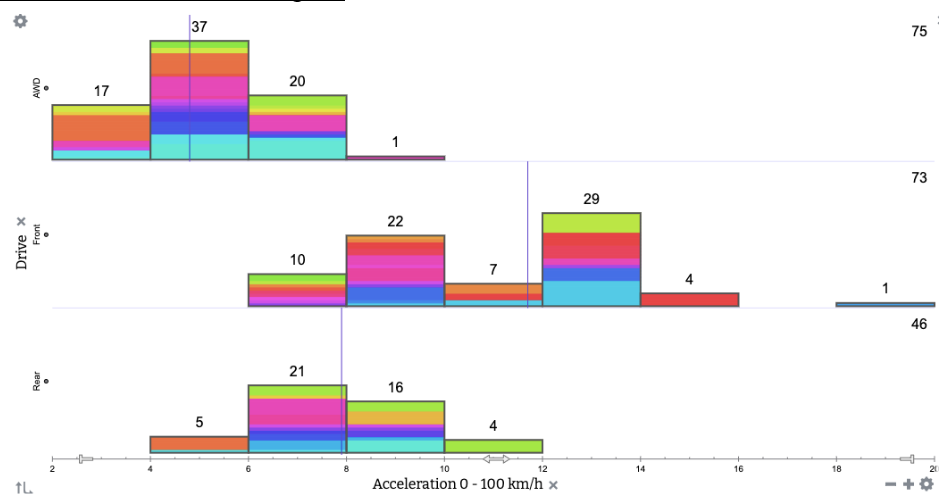

One important aspect of this project is helping students build data literacy. The program identified Tuva as the right partner to help their students explore and analyze the data they have collected and to make the data publicly available. Through the All About Arsenic + project data portal on Tuva, students can access all of the project data or can filter it to show only their school’s results.

“Most of the time in high school science,” Ramgren explained, “you are doing labs that are kind of meaningless in the sense of larger scientific data. No one is interested in the data some kid got about the density of copper.”

In contrast, interest in well water data has been high. Ramgren said test results have spurred some homeowners in his area to install arsenic-removing filters. The Maine Center for Disease Control and Maine lawmakers have been paying attention too.

“You can gather real information as a citizen scientist and actually contribute even if you are ‘only’ a high school student.”

In 2022, data collected by participants in the All About Arsenic program convinced the Committee on Labor and Housing to double their request for funding allocated to well water remediation3.

“It’s real data that people are using to inform public policy,” said Ramgren. “You can gather real information as a citizen scientist and actually contribute even if you are ‘only’ a high school student.”

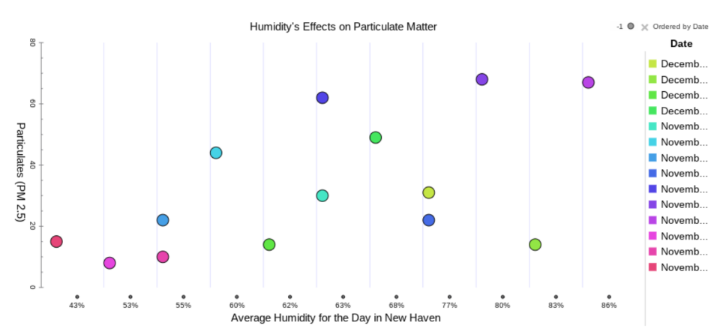

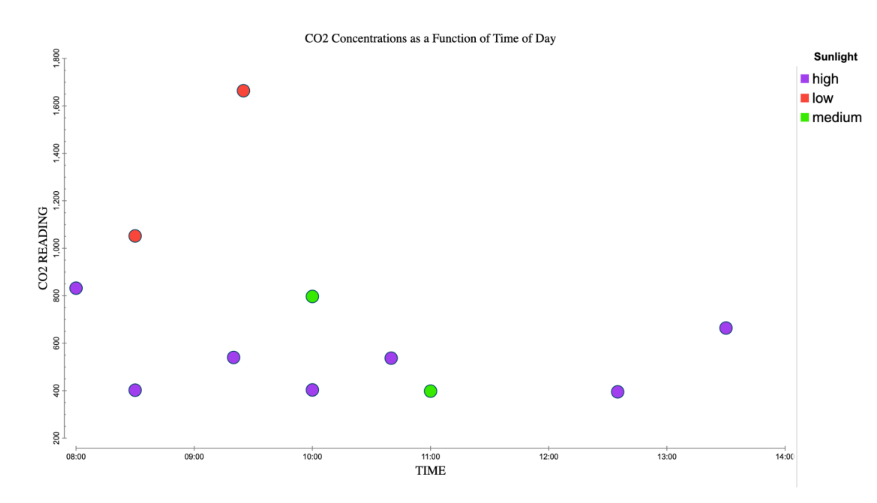

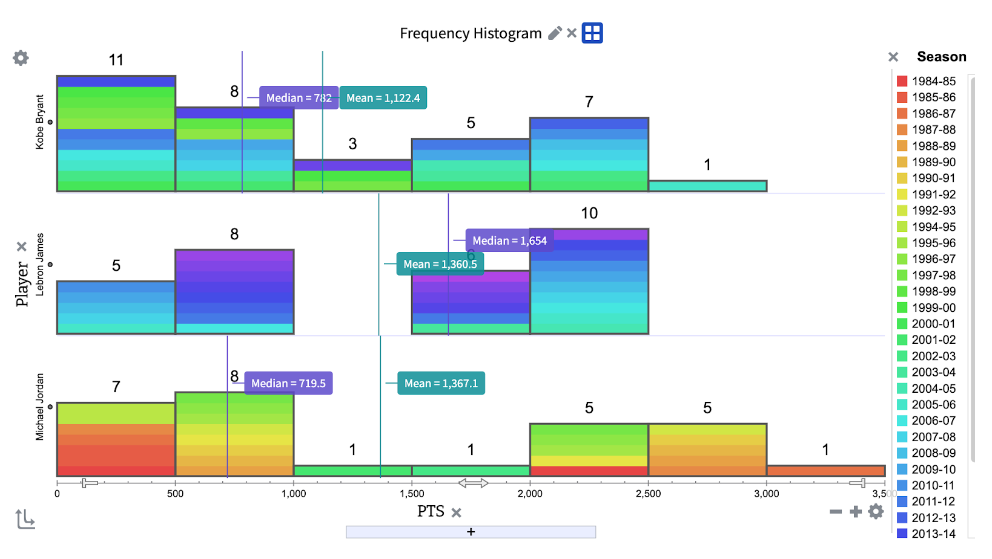

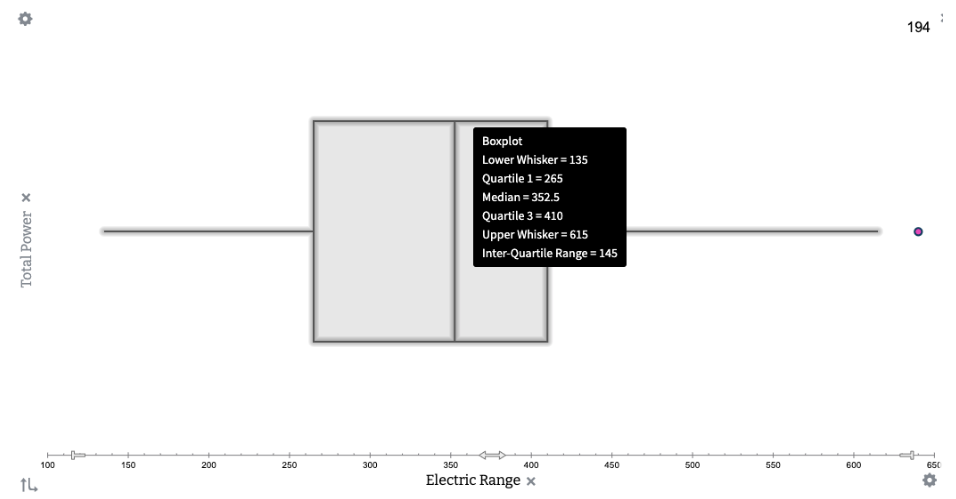

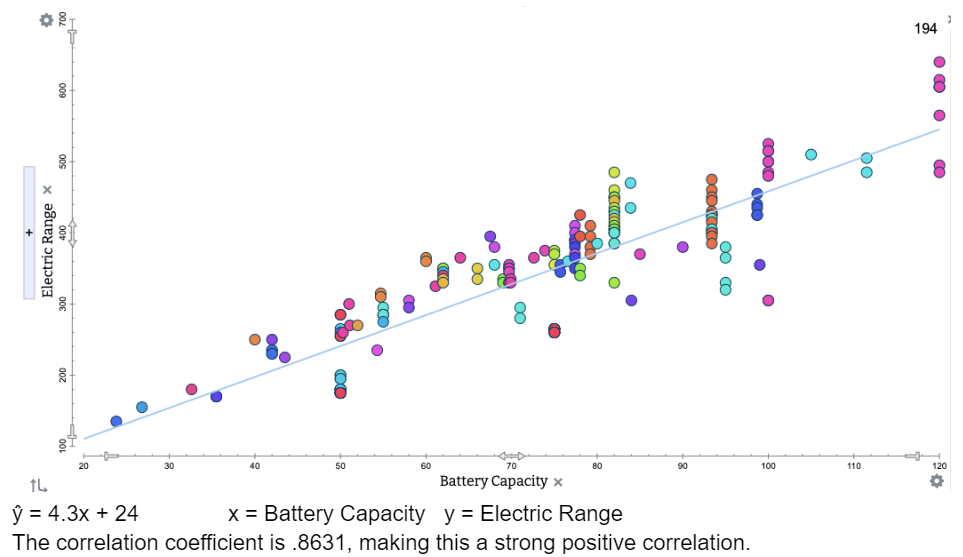

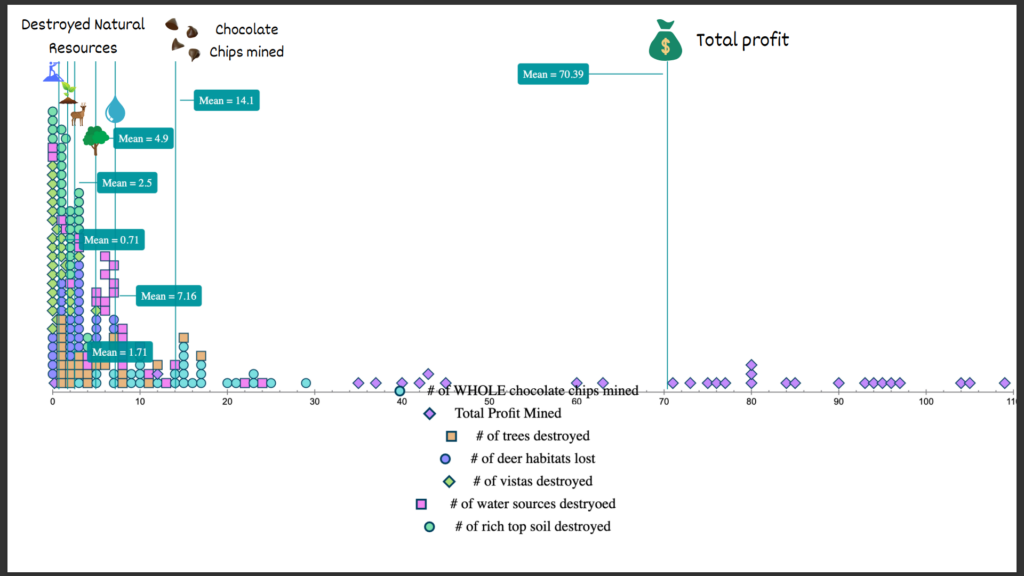

Engaging in citizen science is more time-consuming than using canned labs and textbooks, but Ramgren said the extra time is worth it. Amongst the benefits lauded by Ramgren are stickier learning, authentic problem-solving as students wrestle with how to act upon the data, and a stronger understanding of the nature of science. Collecting and analyzing real-world data, students get a more accurate picture of how professional scientists experience data – with lots of variability, background noise, and messiness. Because creating graphs by hand is so time-consuming, students are often only asked to make graphs when there is a correlation between variables. As a result, students may erroneously expect there will always be a correlation.

But it’s important for students to realize graphs showing a lack of correlation are equally important. The All About Arsenic dataset that’s housed by Tuva includes 28 attributes, or variables. Students can use the Tuva tools to quickly make and explore multiple graphs- both those that show correlation, and those that don’t.

Ramgren is also hopeful that real-world data collection will help students avoid another misconception that plagues our society- the notion that science ideas are absolute and unchanging.

“Science is not static. We are constantly getting new information,” Ramgren said.

He thinks altering the way we teach science can help kids recognize science knowledge is subject to revision and improvement in the light of new evidence. When we have students redo experiments for which the answer is already known, we reinforce the impression that we know everything in science already. However, if students are actively adding to scientific knowledge, they will understand its fluid nature.

- MDI Biological Laboratory. “All About Arsenic+.” All About Arsenic, 2023, https://www.allaboutarsenic.org/sepa/. Accessed 31 October 2023. ↩︎

- Maine Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & Maine Department of Health and Human Services. “Private Well Water | Maine Tracking Network.” Maine Tracking Network, 2021, https://data.mainepublichealth.gov/tracking/private-wells. Accessed 31 October 2023. ↩︎

- Viles, Chance. “Westbrook students’ science project makes impact in Augusta.” The Portland Press Herald, 1 March 2022, https://www.pressherald.com/2022/03/01/westbrook-students-science-project-makes-impact-in-augusta/. Accessed 31 October 2023. ↩︎