California Teacher Spiri Bavelas Trains her Students to Know Their Way Around Messy Data

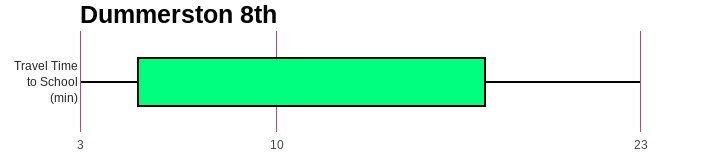

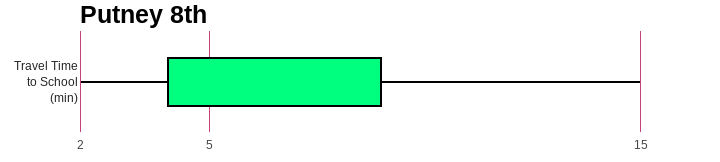

Working with data becomes second nature to students in Spiri Bavelas’ science classroom. Whenever they are completing an experiment in her class, students collect their own data and put it into a shared, class-wide spreadsheet. Then, Bavelas uploads the data into Tuva where students can manipulate and explore it. When Bavelas uses larger, messy datasets, she’s drawing from her years as a research assistant before she began teaching.

“You never are going to look at just five numbers in the real science world.”

“When I started, students collected four or five numbers and were supposed to come up with a big conclusion, but you never are going to look at just five numbers in the real science world,” she said.

Bavelas has worked in a handful of different schools throughout California, but recently took a position at R. Roger Rowe Middle School in Rancho Santa Fe. Wherever she has been, Bavelas has engaged her students with large data sets.

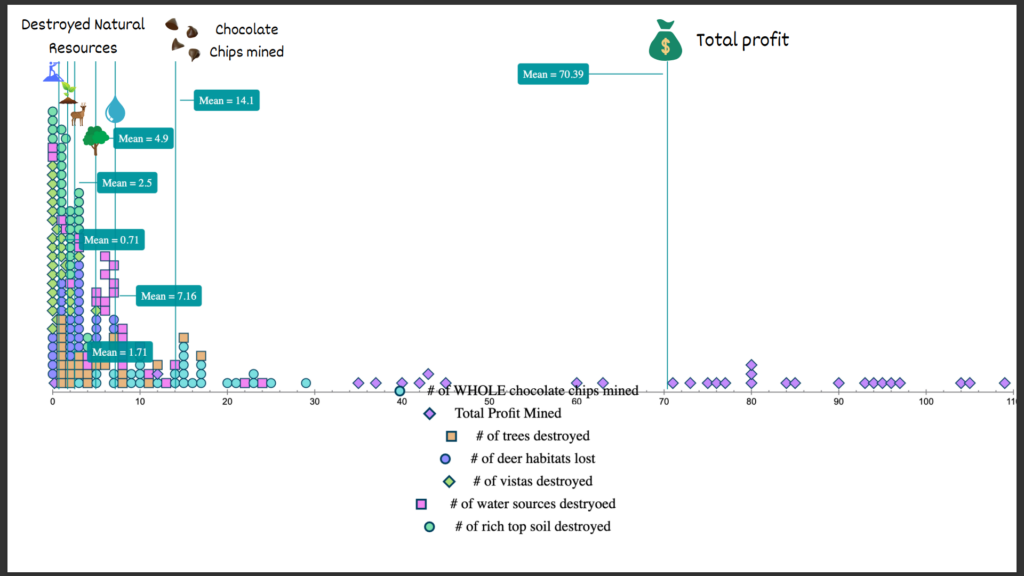

One of the lessons she hopes to impart to her students is that people can use data to make better decisions. Bavelas used a popular mining simulation to illustrate this concept during an environmental resources unit. Students placed cookies on grid paper and mined the chocolate chips, keeping track of expenses and income. Afterward, she instructed them to measure damage to the environment based on the number of grid squares where crumbs landed. By analyzing all of the data pooled from Bavelas’ classes, students gained insights into which mining strategies caused minimal harm, enabling them to develop new, environmentally-friendly, yet still profitable, methods of extraction.

Bavelas also showcased the utility of collective data during an annual egg drop competition at one of her former schools. Engineering teams were awarded points for landing crafts that had a slow descent, hit the target, and kept the egg safe. Bavelas had been collecting egg drop data over multiple years. Students used the data from prior years to inform their design decisions. For example, the data revealed that a light lander is advantageous, but only up to a point. If the device is too light, it drifts off target.

“Data analysis is not just something you can do in one class,” Bavelas said. “Data can be a thing on a larger scale where you can collaborate with people that are not right next to you.”

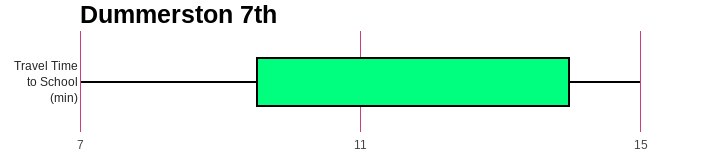

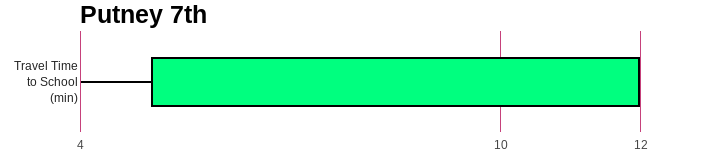

Bavelas also wants her students to be aware that data displays can be manipulated to suggest certain conclusions. For example, she explained, if you look at a bar graph and zoom in on the differences it might look like the more massive car travels down a ramp faster. However, when you look at it on a larger scale, the difference is tiny, and calculations reveal there is no statistical correlation between mass and speed.

Whether it’s understanding the importance of sample size, utilizing data to make good choices, or being savvy enough to detect deceit, Bavelas hopes the lessons students learn in her science class will serve them well in whatever path they choose.

“I want the skills students obtain in science class to be a vehicle for better understanding and functioning in the entire world.”